When something goes wrong, we often seek someone to blame. Sometime the culprit is obvious, as when someone hits you or rams into your car or knocks over your vase. When things go wrong in a pregnancy, it can be harder to tell what happened. But having someone to blame is comforting. Assigning blame allows us to believe that avoiding the blameworthy person’s mistakes will spare us a similarly bad outcome.

Blaming Mothers

People are quick to blame women for any bad pregnancy outcome–miscarriage, preterm birth, still birth, baby with disabilities, baby with genetic disorders, low birthweight baby and on and on and on. Any choice a pregnant or birthing mother makes, it seems, can be used against her. A New York Times piece points out that

much of the language surrounding advice to pregnant women as well as warnings is “magical thinking” that suggests that women who do everything right will have healthy babies — and therefore, women who have babies with birth defects failed to do everything right.

Women are blamed for not following a doctor’s orders, even if those orders have no basis in evidence, such as bed rest to prevent preterm birth.

Women may be blamed for not following folk wisdom: some people strongly believe that a pregnant will miscarry if she lifts anything heavier than a frying pan or that her fetus will strangle on its umbilical cord if she raises her arms over her head.

Women may be blamed if they do follow a doctor’s orders if a bad outcome occurs. Virginia Rutter notes the following case from Paltrow and Flavin’s 2013 article on the criminalization of pregnant women:

A Louisiana woman was charged with murder and spent approximately a year in jail before her counsel was able to show that what was deemed a murder of a fetus or newborn was actually a miscarriage that resulted from medication given to her by a health care provider.

Women may be blamed for choosing a provider or place of birth someone else feels is inadequate. One mother who planned to birth at home with a registered midwife wrote,

If something does go wrong, with the birth, or otherwise, [my mother] is going to blame me forever, for my “selfishness.” If the baby grows up to have a learning disability or something (for whatever reason), my Mom [who had cesareans] is going to say that it’s all my fault for having a natural birth, that I damaged the baby’s brain.

In fact, blame may be heaped on women for things that others believe have the potential to cause poor pregnancy outcomes, even if the actual outcomes are just fine. For instance, women are often pilloried for having so much as a sip of wine during pregnancy, even though the evidence of harm in to the human fetus from low to moderate alcohol use is nearly nonexistent.

Women may even be blamed for things that they no longer do, as was the case with Alicia Beltran, who was imprisoned for refusing medical drug treatment while pregnant because she no longer used drugs.

Blaming Providers

Some OBs openly acknowledge that their colleagues find it difficult to change practice in response to new scientific information–or even old scientific information. Some examples are recommending bed rest, performing routine episiotomies, and using Pitocin for elective induction of labor. However, when a woman or her infant develops a complication from one of these routinely prescribed interventions, the physician is rarely blamed for the poor outcome. In fact, the doctors are often lauded in such circumstances for doing “all they could.”

Doctors claim that women demand potentially harmful procedures, such as elective inductions or cesareans. Ashley Roman, MD, a maternal fetal medicine specialist at NYU Medical Center said, “I have definitely seen an increase in C-section requests, even when there is no real medical justification behind it.” But the Listening to Mothers III survey found, “Despite much media and professional attention to ‘maternal request’ cesareans, only 1% of respondents who had a planned initial, or ‘primary,’ cesarean did so with the understanding that there was no medical reason.”

ACOG actually sanctions elective cesareans (albeit reluctantly). In a 2013 Committee Opinion on elective surgery, ACOG concludes, “Depending on the context, acceding to a request for a surgical option that is not traditionally recommended can be ethical.” Though their 2013 Committee Opinion on maternal request cesarean says vaginal birth should be recommended, it provides parameters for performing an elective cesarean.

Doctors sometime behave as if they are helpless to say no in the face of maternal request for elective medical procedures, such as cesareans or early inductions. The director of women’s services at one hospital with a high early induction rate said,

A lot of the problem was the fear among our physicians that if they didn’t do what the patient asked, they’d go find another doctor. It was a financial issue.

Women, however, report that physicians consistently offer elective inductions and cesareans. On the Evidence Based Birth Facebook page, Megan posted, “I was ‘offered’ an induction at 39 weeks at every visit starting at 34 weeks.” At The Bump, user Ilovemarfa wrote, “I was induced with my son when I went overdue by over a week and he was estimated to be about 10 lbs 5 oz. My doctor offered me a c section due I possible high birthweight…” Her baby weighed 8lbs 9 oz. Note that a prophylactic cesarean is only supposed to be considered if the baby is estimated to weigh at least 11 pounds.

Physicians may act as if they are doing women a favor by offering elective procedures. For instance Emily on Baby Gaga posted,

I’m due [in two weeks]. I went to the doctor today. Last week I wasn’t dilated, but now I am 3 cm. He said if I don’t have the baby by my next appointment, I could pick a day, and they would induce me. No medical reason.

Or the provider may state that the procedure will be done, without any discussion or informed consent process. On the Evidence Based Birth Facebook page, Becca reported, “[My]care provider did routine 36 week ultrasounds. [I] was told I was going to have a ‘Texas sized baby’ and would be induced if labor didn’t start…before 40wks.” Dana was told at 29 weeks that “All first time moms need an episiotomy.”

In their Committee Opinion on Maternal Decision making, ACOG recommends,

Pregnant women’s autonomous decisions should be respected. Concerns about the impact of maternal decisions on fetal well-being should be discussed in the context of medical evidence and understood within the context of each woman’s broad social network, cultural beliefs, and values. In the absence of extraordinary circumstances, circumstances that, in fact, the Committee on Ethics cannot currently imagine, judicial authority should not be used to implement treatment regimens aimed at protecting the fetus, for such actions violate the pregnant woman’s autonomy.

Despite their acceptance of elective interventions and a professional ethics opinion stating that women’s decisions should be respected, physicians sometimes threaten or persecute women when they refuse interventions–whether they are evidence based or not. At the blood-pressure-raising website My Ob Said What?, a woman who told her OB that she refused to schedule a routine C section for her twin pregnancy (not evidence based) reported that she was told,

If you do that, then we’ll have to get social services involved and believe me, you don’t want that, Cookie.”

Another said she was told,

If you don’t agree to the cesarean section, we will call Child Protective Services and they will take the baby away for someone to be a real parent.”

A woman in Florida “was ordered to stay in bed at Tallahassee Memorial Hospital and to undergo ‘any and all medical treatments’ her doctor, acting in the interests of the fetus, decided were necessary.” She was not even allowed to ask for a second opinion (bed rest is not evidence based).

One woman pointed out that doctors are not “reported to social services for child endangerment every time they try to induce a baby who’s not ready to be born, just for their own convenience” but that “if a mother did something for her own convenience that landed her child in the hospital, there sure as hell would be…lots of tough questions, lots of shaming.”

As stated earlier, when bad outcomes happen because of a physician’s choices, people often praise the doctor’s heroic efforts, even if the dangerous situation was caused by the physician.

A prime example is use of Pitocin without medical indication (you can read more about Pitocin here and elective induction here). Some doctors who want to rush a birth or generate a reason to perform a cesarean practice something called “Pit to distress.” Nursing Birth has an in-depth explanation with examples, but the short version is as follows:

- A doctor starts Pitocin to induce labor or augment it (speed it up).

- The dose is raised until the woman is contracting strongly and regularly.

- The doctor orders that the dose keep going up, even though the woman’s contractions are already strong (at least 3 in 10 minutes).

- The uterus becomes “tachysystole,” meaning there are more than 5 contractions in 10 minutes.

- In many cases, not enough oxygen gets to the fetus under these conditions, the fetus goes into distress, and the mother is rushed to the operating room for an emergency cesarean that “saves” her baby.

Many times, the woman has no idea that the physician ordered that her Pitocin dose be raised, so she doesn’t realize that the doctor caused the fetal distress. All she knows is that the baby was in distress, and that her doctor saved the baby from a potentially terrible outcome.

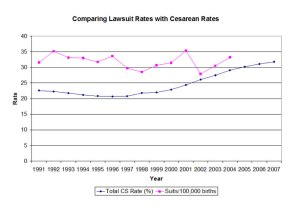

Even when bad outcomes occur, lawsuits are not common. Despite the hype around liability, it doesn’t seem to impact practice the way doctors say it does. After tort reform passed in Texas, limiting physician liability, the cesarean rate continued to go up at more or less the same rate as the rest of the country. As one obstetrical nurse said, though physicians and nurses fear lawsuits, “hospital staff are rarely criminally prosecuted for their actions or inactions.”

Blame, Fate and Social Control

Certainly there may be someone to blame when a pregnancy or birth has a bad outcome. But there may not be. Blaming a doctor is frightening–it encourages people to question someone they need to trust with their lives–and their babies’ lives. Fate can be even scarier–no one controls fate. And in looking someone to blame, it seems society is often more interested in the social control of pregnant women than in rooting out the real culprit. There may be those who escape unscathed, but nobody wins in this blame game.